Introduction

Central serous chorioretinopathy is characterized by a serous retinal detachment (SRD) with the potential for vision loss. There are two primary forms of CSCR: acute and chronic.

Central serous chorioretinopathy affects men more than woman and is most prevalent in Caucasian and Asian populations between the ages of 20 and 50 years old.1

When occurring in patients less than 50 years of age, CSCR is typically unilateral. Older patients are more likely to present with chronic, bilateral disease depending on etiology. Chronic CSCR is associated with diffuse retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) degeneration and has an increased potential for secondary choroidal neovascularization (CNVM) due to the chronicity of the disease process.1

In most cases, CSCR is acute, idiopathic, and self-limiting. However, recurrent SRD can lead to chronic CSCR with features such as RPE dysfunction, persistent sub-retinal fluid (SRF) lasting longer than six months and thinning of the outer retina.2

This case report highlights the clinical presentation and potential complications of chronic CSCR.

Case Presentation

A 73-year-old Caucasian male presented to the eye clinic for a routine eye exam with no visual or ocular complaints. His ocular history was remarkable for ocular hypertension in both eyes treated with latanoprost, and a choroidal nevus in the right eye. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, emphysema, cocaine abuse, and chronic tobacco smoker. He had a pulmonary lobectomy as treatment for lung cancer and his medications included daily oral prednisolone and a daily inhaler, fluticasone propionate/salmeterol.

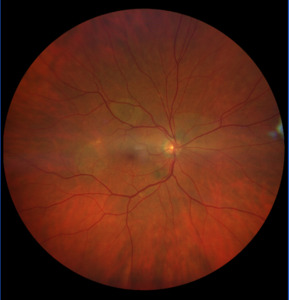

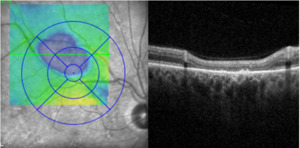

Upon examination, the patients’ visual acuity (VA) was 20/20 in each eye. Pupil testing, ocular motility testing, and confrontation fields were unremarkable. Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed mild cataracts and meibomian gland dysfunction. Intraocular pressures were normal in each eye. Dilated fundus exam revealed three large focal areas of retinal hyper and hypopigmentation in the right eye (Image 1). A retinal optical coherence tomography (OCT) taken over the lesion confirmed an overall thinning of the outer retina superior temporal to the fovea (Image 2). The left eye was unremarkable. The patient was referred to the ophthalmology service for further management.

The patient was diagnosed with chronic CSCR with presumed secondary to chronic corticosteroid use and managed conservatively.

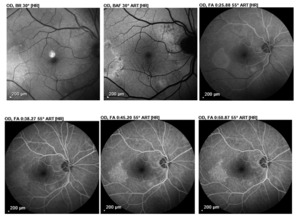

Upon further review of the patient’s case history, it was noted that six years prior to presentation the patient had an area of subretinal fluid (SRF) inferotemporal to the macula. The OCT revealed an area of SRF (Image 3), and fluorescein angiography (FA) showed a large focal area of pooling consistent with CSCR (Image 4). No treatment was indicated at that time and the patient was referred by the retina service for routine eye care.

Discussion

This case highlights the clinical features and management of chronic CSCR. The patient presented with retinal pigmentary changes and RPE atrophy, which were further highlighted on OCT and FA. The patient had excellent VA as the CSCR lesions were extrafoveal and he was managed conservatively.

Pathophysiology

In most cases, CSCR is acute, idiopathic, and self-limiting. However, recurrent SRD can lead to chronic CSCR with features such as RPE dysfunction, persistent SRF lasting longer than six months, and thinning of the outer retina.2 The recurrent SRF is hypothesized to result from increased capillary permeability of the choroid, which can be caused by increased levels of cortisol in the blood.3 Chronic use of systemic corticosteroids and corticosteroid sprays or inhalants, eye drops, and topical creams can also lead to recurrent SRF and chronic CSCR.4

The proposed mechanism of action of corticosteroids in CSCR involves the RPE and choriocapillary mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) activity. Steroids lead to excess activation of the MR in the choroid and relaxation of the smooth muscle in the choroidal vasculature. Over time, this impacts the posterior blood-retinal barrier, resulting in focal areas of increased permeability of the vessel walls and SRF.3

In an SRD, the retinal photoreceptors are separated from the RPE. In acute cases, the SRF provides sufficient nutrients to the photoreceptors, which can allow them to remain undamaged. However, if the SRF persists for greater than six months, ischemic damage of the photoreceptors can occur as in chronic CSCR.3

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of CSCR includes age-related macular degeneration, vitelliform macular dystrophy, diabetic macular edema, or cystoid macular edema (Table).

Diagnosis

Clinically, a patient with acute CSCR commonly presents with a unilateral serous macular detachment. In chronic CSCR, the fundus exam typically shows a shallower SRD with retinal hypo/hyperpigmentation due to the disruption and alteration of the RPE.1

Diagnostic tools such as OCT, fundus autofluorescence, and FA can be used to differentiate CSCR between other common retinal conditions such as those listed above. Optical coherence tomography reveals the presence of SRF typically at the macula. Other OCT findings consist of focal RPE defects or retinal pigment epithelial detachments (PED).1

Fundus autofluorescence can help localize the disease, estimate chronicity, and predict visual outcomes. Early CSCR shows no pattern or is hypofluorescent due to SRF blocking the signal. In early chronic CSCR there are patches of hypo/hyperfluorescent appearing due to accumulation of photoreceptor outer segments being shed into the SRF; with additional time, there is diffuse hyper-autofluorescence as the patchy accumulation of photoreceptor outer segments become more uniform; in late chronic CSCR, mixed hyper and hypo-autofluorescence is observed secondary to RPE atrophy.1 This finding is typically correlated with decreased visual acuity.

Two classic FA patterns associated with CSCR are the inkblot and the smokestack.4 These patterns are more commonly associated with acute CSCR. The inkblot pattern is a circular area of hyper-fluorescence originating from a central pinpoint and is the more common of the two patterns. The smokestack pattern is an ascending hyper-fluorescence followed by lateral diffusion at the superior margin of the SRD.8 In chronic CSCR, diffuse RPE damage may be present, and FA may show multiple points of indistinct leakage due to increased transmission from window defects from localized RPE atrophy.1

Management

The management of patients with chronic CSCR can be challenging. For patients on steroid medications, it is important to work with their prescribing physician to consider suspending or replacing those medications to help prevent progression of the SRF or recurrent serous macular detachments.

Many treatments have shown minimal visual improvement compared to observation alone.1 In severe cases of chronic CSCR, photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a treatment option.9 Ocular PDT can reduce the recurrence of SRF, though visual outcomes from PDT vs. observation are similar.1 Patients with chronic CSCR are at risk for developing secondary CNV. Secondary CN is treated with intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy.1 Research on systemic medications that block corticosteroid receptors are promising in preventing recurrences of SRF.1 Medications like spironolactone and eplerenone have shown to reduce central retinal thickness and improve visual acuity in patients with chronic CSCR.10 These medications are MR antagonist and bind to the MR to prevent glucocorticoids or corticosteroids from binding. This has been shown to cause a faster absorption rate of SRF.10

Conclusion

Chronic CSCR is characterized by several clinical features, including recurrent SRF and outer retinal atrophy, which can lead to permanent vision loss. In cases of CSCR linked to systemic medications, an interdisciplinary approach with the patient’s prescribing physician is essential. Patient education, the use of a home Amsler grid, and continued follow-up plays a key role in monitoring for complications such as RPE disruption and CNV formation as these can lead to permanent vision loss. For patients with permanent vision loss, a referral to a low vision specialist will help them utilize their remaining vision.

Disclosure

There are no financial or personal interests to disclose.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.