Introduction

Neurotrophic keratitis (NK) is a rare and potentially blinding condition with a high potential for causing thinning and scarring of the cornea. This condition can be difficult to treat. Corneal perforation, endophthalmitis, and blindness or loss of an eye are possible sequalae. The rate of NK in the population is estimated to be between 1.6 to 5 in 10,000 individuals.1–4

The cornea is innervated by the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve. Neurotrophic keratitis is caused by damage to the trigeminal nerve causing decreased reflex tearing and loss of corneal sensitivity.1–9 Numerous other factors contribute to the severity of NK.1,2,5,6 These factors include corneal injury, infectious agents including bacteria, virus, fungus, parasites. If nerve function is not restored, the corneal epithelium will deteriorate further until ulceration occurs.

The cells of the cornea must receive nourishment from other sources due to the cornea’s avascular nature. The aqueous fluid in the anterior chamber and the tears on the anterior surface of the eye provides nutritional components necessary to maintain cellular integrity. Atmospheric oxygen as well as oxygenated blood in the palpebral conjunctival vessels provide nourishment to the cornea. Key to this process is the tears that transport oxygen as well as lubricate and maintain cellular hydration of the anterior portion of the cornea.10 As the tissue becomes desiccated, the epithelium begins to break down. The loss of corneal sensation can be so pronounced that formation of an open lesion on the corneal surface may not even be noticeable.

Understanding the underlying pathophysiology helps clinicians make the most appropriate treatment decisions to halt progression.1,3,6,7,11 It is essential that optometric physicians are able to recognize and differentiate NK from other conditions affecting the cornea.

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old Caucasian male presented to the optometry clinic at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center for dry eye follow-up on a Friday afternoon. His initial complaint was blurred vision with a constant moderate sharp stinging sensation in the left eye for the past three weeks. The patient presumed it was caused from air leaking into his eye from wearing a CPAP mask during the night. He was using copious amounts of artificial tears during the day and ointment at bedtime in both eyes. Associated signs and symptoms included photophobia, conjunctival injection, crusting on the lashes, and dry eyes.

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for numerous autoimmune conditions including Sjogren’s syndrome, mixed connective tissue disease, and Raynaud’s disorder. The patient’s thyroid gland was previously removed following a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Other medical issues included bilateral lower extremity neuropathy, osteoarthritis in both knees, morbid obesity, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), gastroesophageal reflux disorder, hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, migraine headache, history of aortic aneurysm repair, mechanical prosthetic aortic valve, and diastolic heart failure. Current systemic medications included folic acid, warfarin, sildenafil, pregabalin, potassium chloride, omeprazole, nortriptyline, methotrexate, losartan, hydroxychloroquine, furosemide, duloxetine, cevimeline, acetaminophen, and vitamins D and B-12.

Pertinent ocular history included keratitis sicca/dry eye associated with Sjogren’s syndrome and an optic nerve appearance suspicious for glaucoma damage. The patient had bilateral lacrimal puncta cauterization in the early 1990’s. His most recent dilated eye examination was nine months prior showing grade 1-2+ superficial punctate keratitis in both eyes. He was wearing bifocal glasses with a light brown tint. The patient noted that his xerostomia (dry mouth) and dry eye symptoms were improved with the use of cevimeline, a cholinergic agonist.

Entering distance visual acuity was 20/20- in the right eye and 20/150 in the left eye. The patient had a mild astigmatic correction, the left eye being worse. Pinhole vision in the left eye was 20/60-. Pupils were equally round with a more brisk response to light in the right eye and no afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular motility was smooth and full in both eyes. Cover test showed orthophoria at near.

Anterior segment examination via slit-lamp was remarkable for 3+ conjunctival injection, a 2.75 mm round corneal ulcer inferior temporal to the visual axis with an excavated center, and staining with fluorescein dye in the left eye. There was neovascularization of the cornea from 3:00 to 5:00 encroaching onto the cornea (See Figures 1 and 2). Other findings included cauterized puncta, a deep and quiet anterior chamber, and trace mixed age-related cataracts in both eyes. Intra-ocular pressure readings were 8 mmHg in the right eye and 10 mmHg in the left eye via Tonopen.

Management and Outcome

The patient’s initial complaint of blurred vision was deemed to be directly related to the corneal ulcer. Best practices for management of a corneal ulcer include culturing for an infectious cause, coverage with frequent fluoroquinolone dosing, and monitoring every 24 to 48 hours.4,6,8,9,12–14 The differential diagnoses considered were bacterial, viral, and fungal infection, keratoconjunctivitis sicca/dry eye. Neurotrophic keratitis was also considered due to the patient’s significant medical history for autoimmune conditions including Sjogren’s with sicca and his lack of significant pain and photophobia.

A referral to ophthalmology was made and the patient was evaluated 2 hours later. Based on the ophthalmologist’s report, the previous history was remarkable for three weeks of blurred vision and pain in the left eye. His visual acuity was 20/150 in the left eye with pinhole acuity to 20/60-. Their findings included a 2.9 mm round corneal ulcer in the left eye with 20% thinning. They cultured the ulcer and began moxifloxacin drops every two hours with instructions to follow up two days later. The evaluation 2 days later showed that the corneal ulcer in the left eye was stable but not improving. The patient was instructed to continue with moxifloxacin drops every two hours and continue using lubricating ointment at bedtime.

The patient was seen the following day reporting that his left eye had improved; he was not reporting any eye pain, only a little stinging. The slit-lamp findings included a 2.6 X 2.2 mm ulcer with inferior neovascularization, 1+ conjunctival injection, no hypopyon, a negative Seidel sign, and 1-2+ anterior chamber cells. He was instructed to continue using the moxifloxacin drops every 2 hours; the lubricating ointment at bedtime was changed to Bacitracin ointment.

He was seen again two days later with no improvement in his vision (20/100 with pinhole to 20/70). The results of the cultures showed no growth to date for bacteria and an unacceptable fungal culture. The slit-lamp findings were stable except for no cells or flare in the anterior chamber. The assessment showed that the ulcer was less likely to be infectious and more likely to be neurotrophic. The patient’s history of Sjogren’s and OSA were likely contributing to poor healing of the neurotrophic ulcer. The moxifloxacin drops were reduced to four times daily, the Bacitracin ointment was replaced with Erythromycin ointment to be used six times per day, and vitamin C 1000 mg daily were added. The patient was instructed to use preservative free artificial tears every hour in his left eye. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was considered, however it was contraindicated in this patient due to interference with his other systemic medications (i.e., Warfarin).

Five days later the patient stated that he accidently stuck his thumb in his left eye and felt fluid on his cheek. He returned to a different ophthalmologist who diagnosed a corneal perforation and used cyanoacrylate glue with a bandage lens to seal the leak and inflate the anterior chamber. The cornea perforated again the following day and he returned for repeat treatment with cyanoacrylate glue, a new bandage contact lens, and inflation of the anterior chamber. The following day his anterior chamber was observed to be formed with the corneal glue and bandage contact lens in place. His visual acuity was counting fingers with pinhole to 20/200.

He was instructed to continue with the bandage contact lens, cover his eye with a metal eye shield, and reduce the moxifloxacin drops to four times daily. The patient returned 2 days later with a complaint of light sensitivity and some yellow-colored pus discharge. The final bacteriology report showed no growth to date with unacceptable mycology testing. His anterior chamber was still formed, but extremely shallow and the bandage contact lens was still in place. His vision was 20/400 with pinhole to 20/150. Ophthalmology recommended continuing the moxifloxacin drops 4 times daily and vitamin C 1000 mg daily. He was referred to the Rheumatology clinic to evaluate the need to alter the Methotrexate dose as it related to his mixed connective tissue disease and corneal thinning.

The patient was seen weekly for the next month. He continued wearing a bandage contact lens, using the moxifloxacin drops, Erythromycin ointment, and taking vitamin C. It was noted that the corneal glue and bandage contact lens were in place. The anterior chamber was deep and well formed. The vision was stable at 20/150+ (no improvement with pinhole). The erythromycin ointment was discontinued, the moxifloxacin reduced to twice daily, and the vitamin C was continued. Three weeks later the corneal epithelium was healed leaving a scar with neovascularization inferiorly. The patient’s vision had improved to 20/40 with pinhole. The moxifloxacin was discontinued, and the patient continued taking vitamin C along with preservative free artificial tears and ointment.

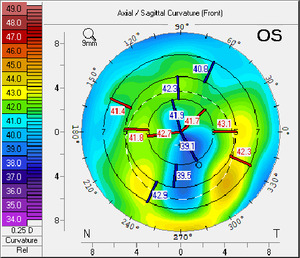

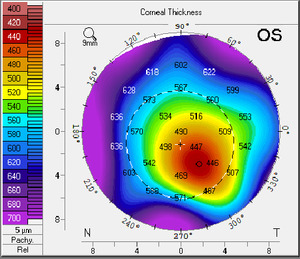

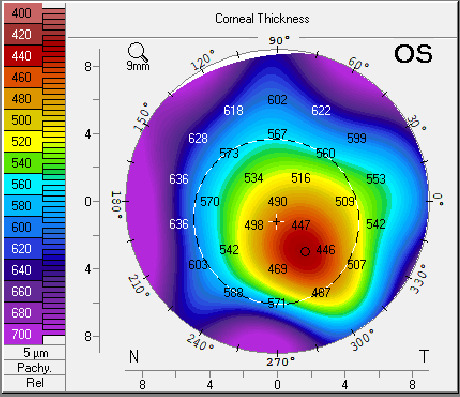

The patient was seen two more times in the next two months with stable vision and corneal findings. He was given an updated prescription for glasses and fitted with scleral contact lenses which improved his vision and comfort. An external image of the patient’s left eye was taken prior to the fitting of his scleral contact lenses (Figure 3). The topography image shows the residual thinning and irregular astigmatism following treatment of the neurotrophic ulcer in the left eye (Figures 4 and 5). The visual acuity in the left eye was 20/30 with the scleral contact lens.

Discussion

The cornea is innervated and nourished by the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve, which is responsible for maintaining corneal hydration and sensitivity. With a lack of sensitivity, the cornea can become compromised. Symptoms of NK may mimic those of other ocular surface diseases with the primary distinguishing factor being a disproportionately high number of signs compared to symptoms.1–4 This was true with the patient in this case report who came in primarily because of fluctuating blurriness of vision.

NK is separated into stages as the disease progresses. Stage one is characterized by decreased corneal sensitivity, punctate staining, decreased TBUT, dellen, Gaule spots (scattered areas of dried out epithelium), and stromal scarring. In stage two, epithelial breakdown begins to occur. It is characterized by persistent epithelial defects and stromal swelling which may lead to ulceration. With stage three, the cornea begins to experience stromal break down or thinning (also called stromal melting). At this stage, corneal ulcers may form which can progress to corneal perforation.1,5,6

The most common causes of damage to the trigeminal nerve are herpetic infections followed by trauma, chemical burns, and residuals of high fever. There are other causes including different disease states which can contribute to nerve damage. Many of these diseases are autoimmune disorders, such as Sjogren’s syndrome, where the body’s immune system begins to attack itself.4–7,9

Decreased tear production and increased evaporation lead to chronic dryness and inflammation which damages the surface of the eye. The compromised ocular surface is then predisposed to thinning and perforation which are the end stages of Neurotrophic keratitis. There are other autoimmune conditions that can damage the nerves to the eye and particularly to the cornea and lacrimal system. They include Rheumatoid Arthritis, Mixed Connective Tissue Disorder, Graves’ Disease, Lupus and more.15–19 Referral to or communication with a Rheumatologist is recommended for management of rheumatological disease with immunosuppressant drugs.11,15,16,20

Diagnosing NK

Diagnosing NK is very different than diagnosing other forms of keratitis caused by infection, trauma, and other conditions. For example, bacterial keratitis will have an associated mucus discharge, redness, pain, and discomfort. With herpes simplex keratitis, dendritic corneal lesions, and skin lesions on or around the eyelids are common. In cases of infective keratitis, an offending agent can be found via culturing. Patients with infective keratitis know there is a definite problem because of significant discomfort and pain from inflammation surrounding the eye.

In NK there are several distinguishing characteristics usually present. The hallmark finding in nearly all patients with NK is decreased corneal sensitivity.1–6,8–10 Other findings include a disproportionate number of ocular signs to symptoms. The signs align closely with that of dry eye syndrome or exposure keratitis. Unfortunately, because of the decreased sensitivity, many NK patients delay seeking treatment until the condition is quite advanced. Rather than seeking treatment for relief of pain, it is more common to seek relief from blurred vision.

If NK is suspected the following tests and procedures are recommended to help confirm the diagnosis and develop an effective treatment plan.1,3–6,9,21

-

A complete health and ocular history including past trauma, chemical burns, high fevers, infections, and eyedrops, both prescription and over the counter

-

A slit-lamp exam of the anterior segment paying special attention to any previous herpetic lesions/scars or any previous ocular laser surgery.

-

Corneal sensitivity testing using a Cochet-f corneal esthesiometer. A cotton wisp or dental floss may also be used if a corneal esthesiometer is not available.

-

Corneal topography to evaluate corneal thinning and irregular astigmatism.

-

Confocal Microscopy to look at the corneal structure on a cellular level.

-

Cultures to rule out infective agents such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites.

-

Lacrimal function including Schirmer’s testing, and tear film break up time is extremely useful in diagnosing NK.

-

A careful review of systems looking for autoimmune diseases, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, vitamin A deficiency, and leprosy.

Our patient presented in the typical fashion of someone with neurotrophic keratitis. His chief complaint of blurred vision is common, and the secondary complaint of moderate stinging was likely due to dry eyes secondary to CPAP use. His corneal sensitivity was diminished, and he had no idea that he had an open lesion on his cornea. The medical history was key in diagnosing NK as the cause of his corneal ulcer which became the focus of the treatment.

Treating NK

Treatment should be directed towards relieving the signs and symptoms. Initially, all topical medications should be discontinued as the medications and/or any preservatives may be causing corneal compromise. The second step is to lubricate the cornea with preservative free tears, gels, and ointments. This will help prevent desiccation and further corneal breakdown. A topical antibiotic is often prescribed as a prophylaxis against bacterial infections. Topical or oral antivirals are used when signs of active Herpes Simplex or Herpes Zoster Viral keratitis are present.

The initial approach taken with our patient was ruling out an infectious cause with culturing of corneal scrapings and then frequent dosing with a fluoroquinolone (Moxifloxacin, which is also preservative free). Preservative free lubricants were increased, and all other topical medications were discontinued. Additionally, vitamin C was prescribed, and Doxycycline considered but rejected due to the patient’s blood thinning medication Warfarin.

Cenegermin is a recombinant human nerve growth factor which supports corneal innervation and integrity. Clinical trials with cenegermin have shown complete corneal healing in 70% of patients treated who had been diagnosed with NK.22 Unfortunately, cenegermin was not available when our patient developed his neurotrophic ulcer.

Vitamin C has been shown to be effective at reducing the scarring of the cornea and beneficial for speeding up the healing process of NK.23,24 Doxycycline has also been shown to speed up repair and healing of the cornea by decreasing matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which decrease levels of inflammatory cytokines.25–27 Tarsorrhaphy (partially sewing the eyelids closed) is an effective method to keep the cornea hydrated and oxygenated.

Newer technology using an amniotic membrane with a covering bandage contact lens which has shown great efficacy in healing damaged corneas.28,29 At the time the patient was seen, amniotic membranes were available but not widely used for this condition, thus it was not considered.

Complications of healing

Ophthalmology was concerned that the patient’s sleep apnea was contributory to poor healing of his neurotrophic ulcer. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has been associated with poor wound healing and is a risk factor for eye disease.

There was also concern that the patient’s connective tissue disorder was not adequately controlled thus causing the cornea to thin rapidly. The rheumatologist consulted was not aware of cornea/scleral issues with mixed connective tissue disease and advised against adjusting the patient’s methotrexate.

Corneal ulcer formation and or perforation can lead to several serious problems including corneal thinning, scarring, corneal irregularities, loss of best corrected vision, total loss of vision, and even loss of the eye itself. Frequent and careful monitoring of this condition is essential.

It is important to educate the patient about the complications during the initial visit, which will help improve patient compliance for treatment and follow-up. Developing a close working relationship with an ophthalmologist skilled in treating NK or a corneal specialist is important. If the treating physician feels that corneal ulceration due to NK is rapidly deteriorating and corneal perforation is imminent, prompt referral is necessary.

Despite following the best recognized treatment protocols, our patient’s cornea perforated within 10 days of initiating treatment. Corneal perforation is an ocular emergency, and it is critical to seal the cornea to prevent intra-ocular infection. The patient was referred to ophthalmology for treatment and regained his vision after a lengthy process of treatment and close monitoring.

Conclusion

NK is a rare and often serious corneal condition. Clinicians must be able to distinguish this condition from other forms of keratitis. The value of a thorough case history and a need for corneal sensitivity testing helps to distinguish NK from other causes of keratitis. NK can be difficult to treat. Complications can occur leading to scarring and thinning of the cornea. The cornea is susceptible to rupture potentially causing a complete loss of vision. Treatment often involves coordination of care with multiple specialties including optometry, ophthalmology, and rheumatology.

In this case, referral was the best strategy because of the patient’s complicated medical history including poly auto-immune disease. The treatment strategy used was effective and the eye healed without any loss of vision. While some scarring is still present, the outcome was remarkably good. NK patients with auto-immune conditions are at higher risk of developing NK again. It is important for them to recognize symptoms of this condition and seek care promptly.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in any material or method mentioned in this article. This article has been peer reviewed.