Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa is a group of inherited retinal dystrophies that cause progressive vision loss and eventual blindness in those affected.1 This paper discusses a case in which a patient with retinitis pigmentosa undergoes Goldmann Visual Field testing and a low vision evaluation, and the data collected qualified the patient for a designation of visual disability under the guidelines set forth by the Social Security Administration and informed discussions on low vision rehabilitative resources, namely orientation and mobility training.

Case Report

Initial Visit

A 38-year-old Middle Eastern male patient was referred for a low vision evaluation and Goldmann Visual Field after electrodiagnostic testing and genetic testing confirmed a diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa. The patient noted that his symptoms of progressive night blindness and peripheral vision loss began in childhood, and he was diagnosed with suspected retinitis pigmentosa around age 12. His family ocular history was unremarkable. His medical history was remarkable for hypertension controlled with low-dose lisinopril. His family medical history was unremarkable, and he denied any allergies to medications. At this visit, his visual acuity was measured to be 20/30 in both eyes as assessed with a Snellen Acuity Chart with his habitual correction.

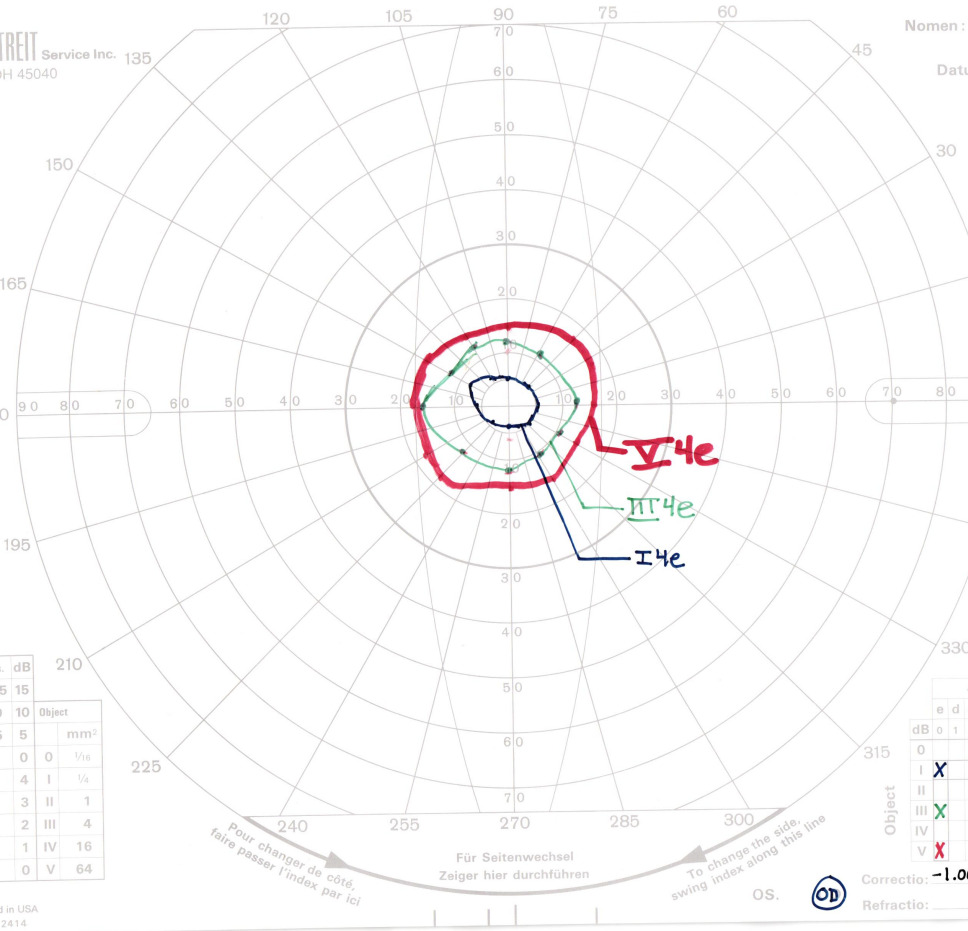

The Goldmann Visual Field was assessed undilated with trial lenses equivalent to a 3.00D add over his habitual correction. There was no loss of fixation in either eye. The test demonstrated significant constriction consistent with a diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa. The right and left eyes showed similar sensitivity losses with each bright isopter along all major meridians. As expected, smaller target sizes caused more significant constriction. There were no temporal islands of vision or central scotomas detected. Approximations of field diameter, as seen in Figures 1 and 2, were 30 degrees in the right eye and 24-32 degrees in the left eye with a V4e stimulus (largest spot size), 23-29 degrees in the right eye and 22-25 degrees in the left eye with a III4e stimulus (medium spot size), and 10-13 degrees in the right eye and 8-14 degrees in the left eye with a I4e stimulus (smallest spot size).

The III4e spot size is the standard used to determine legal blindness, with criteria being the widest field diameter in the better seeing eye must be no greater than 20 degrees. The patient did not qualify for legal blindness based on this definition. However, the Social Security Administration set laws surrounding the criteria for a separate designation titled “visual disability,” which identifies an individual whose visual functioning is equivalent to legal blindness.2 There are two sets of criteria to determine visual disability: a visual efficiency score of 20% or less or a visual impairment score of 1.00 or greater.2

The visual efficiency criteria is required when assessing a patient with a kinetic visual field. Per the Social Security Administration, visual efficiency is defined as: “a calculated value of your remaining visual function, […] the combination of your visual acuity efficiency and your visual field efficiency expressed as a percentage.”2 The visual acuity efficiency percentage corresponding to the best-corrected distance acuity in the better eye of 20/30 is 90%, according to the guidelines detailed in Table 1.2

Visual field efficiency is a percentage that corresponds to the visual field in the better eye as assessed with kinetic perimetry.2 Visual field efficiency percentage is calculated by adding the radius of the remaining field in degrees along the eight principal meridians found on a visual field chart (0, 45, 90, 135, 180, 225, 270, and 315 degrees) in the better eye and dividing by 5.2 By this definition, the visual field efficiency was calculated to be 20.4% in the right eye and 19% in the left eye. An example of this calculation in the right eye is illustrated in Figure 3. Using the better seeing right eye, this value was multiplied by the visual acuity efficiency value of 90% to arrive at a visual efficiency value of 18.36%, qualifying the patient for a designation of visual disability. At this time a formal statement of visual disability was issued, and an in-depth discussion took place regarding the benefits that he is entitled to as a result of this status, including reduced federal income tax. He was encouraged to share his statement of visual disability with his tax professional. Psychosocially, this designation can often be difficult for patients for process. While initially surprised and disheartened by this label, the patient was very understanding after it was clarified that visual disability is a medico-legal definition and not a commentary on his functioning or self-worth.

Follow-Up

The patient returned for a functional evaluation where he reported no difficulties with day-to-day household tasks or work. His main goal for the visit was determining when he should begin limiting or altogether discontinuing driving. The patient still felt safe driving during the day and denied a history of traffic accidents. However, he admitted that occasionally a car or pedestrian would “come out of nowhere.” The patient had no history of using optical aids other than single vision distance glasses. He reported utilizing larger fonts on electronic devices and blue-blocking screen filters.

In unfamiliar areas, he reported exercising caution when navigating and some mild difficulty detecting curbs and stairs. He has never worked with an orientation and mobility specialist. On gross observation, he ambulated confidently and independently from the waiting room to the exam room.

His visual acuities were assessed with a Bailey-Lovie Acuity Chart through his habitual glasses and were 20/32 monocularly in the right and left eye. No improvement in vision was found with retinoscopy or trial frame refraction. A reading assessment was performed using the patient’s habitual correction, an LED overhead task lighting, and a Bailey-Lovie reading card with non-continuous words at a 3rd grade reading level. The patient was permitted to self-select a working distance that he felt comfortable at. At threshold, with maximum effort, the patient could read 0.63M print at 30 cm. At that working distance, a notable decrease in reading speed and efficiency was observed at print sizes below 1.0M print (8-point font).

When investigating the utility of monocular telescopes or near magnifiers, low vision practitioners typically set a goal of 20/40 vision at distance, corresponding to the typical print size observed on road signs and other common distance targets in day to day life, as well as the ability to efficiently read 1.0M print at near, corresponding to the print size observed on many newspapers, magazines, and other common reading materials. The patient already met these visual goals with single vision glasses, so was not assessed with any distance or near magnifying devices. However, a 2.5x monocular telescope was demonstrated to the patient with instructions to look through the objective lens, causing a minification effect. While reducing acuity to a theoretical value of 20/80, this minification can lead to visual field expansion that can help some patients with restricted visual fields orient themselves in new environments. However, this patient did not appreciate the utility of the demonstration.

Weber contrast sensitivity was assessed with a Mars Letter Test. With an LED task light used to mimic photopic conditions, the patient read 42 letters (2.1% Weber contrast). In low luminance conditions, simulated using a 4% transmission gray filter, the patient read 35 letters (4% Weber contrast). Normal Weber contrast sensitivity is 2.0% or less, which suggests near normal contrast sensitivity in room lighting and mildly reduced contrast sensitivity in low luminance conditions.

Ultimately, these findings indicate that, with proper illumination, visual acuity and contrast sensitivity are not significantly limiting the functional vision of the patient. However, it was discussed that the extent of peripheral field constriction will make traveling independently and navigating unfamiliar environments difficult, and an assessment with an orientation and mobility specialist was strongly recommended to determine if training and white cane use may allow for safer, more independent travel. One important consideration for recommending this training is that despite reporting little difficulty navigating his environment currently, these will be useful skills to build now since it is expected that his field constriction will progress in the future.

Because the patient qualified as having a visual disability, which is considered functionally equivalent to legal blindness, it was also determined that the extent of visual field constriction was too great to allow for safe driving, and the patient was instructed to discontinue driving. Conversations with patients surrounding their ability to drive safely should always be held with compassion and with the safety of the patient, their passengers, and everyone around them in mind. Further discussion revolved around ways the patient can limit his driving, including having his wife drive whenever possible and the possibility of a transition to a work-from-home modality at his current job, using his statement of visual disability as evidence of his need for accommodations. Alternative transportation options he was entitled to as a result of his visual disability were also reviewed, including a local paratransit service and discounted rates on public transportation through the Bay Area Rapid Transit system.

Finally, the importance of continued ocular health monitoring with his current primary care optometrist was emphasized. The patient was instructed to return to the low vision clinic as needed should his vision or visual demands change, and continued monitoring with automated perimetry was deemed appropriate due to the extent of visual field loss and lack of peripheral islands of vision.

Discussion

Retinitis pigmentosa occurs in 1 in 4000 individuals in the US and is the most common inherited retinal dystrophy.1 Classic symptoms of retinitis pigmentosa include clinical nyctalopia and progressive peripheral visual field constriction.1 Visual field loss is initially mid-peripheral, and many patients exhibit temporal islands of spared vision early in the course of progression.1 As the condition progresses, however, peripheral islands of vision collapse and a wave of rod death towards the more posterior retina can culminate in eventual cone death and loss of central vision as well.1

Patients with retinitis pigmentosa have extremely varied ages of onset, rates of progression, and clinical presentations. In some cases, retinitis pigmentosa can present during early childhood. More commonly, it develops during the first or second decade of life.3 Central vision may be spared in certain individuals, with current studies suggesting that of patients aged 45 and older, 52% have an acuity of 20/40 or better in at least one eye.4 However, some individuals will have more profound central vision loss, with the same study showing 25% of patients having an acuity of 20/200 or worse in both eyes, and 0.5% of patients having no light perception in either eye.4

Current treatment options for retinitis pigmentosa are limited and primarily focus on treating the other ocular complications that can arise, including posterior subcapsular cataracts and cystoid macular edema. The voretigene neparvovec gene therapy is the first and only FDA approved treatment in the US that can stop the progression of the disease or partially restore vision.5 However, it only treats individuals with biallelic mutations in the RPE65 gene, which account for approximately 2.39% of cases.6–8 While the improvement in functional vision and navigational abilities can have a profound impact on the quality of life of these patients, gene therapy treatments will continue to be limited by the condition’s heterogeneity. Extensive research on treatment options for retinitis pigmentosa is ongoing, and some potential future gene-agnostic treatment options include optogenetic therapy, oral antioxidants, neuroprotective therapies, and retinal transplantation.

Low vision services in cases of retinitis pigmentosa focus on assisting patients with advanced vision loss or legal blindness with devices and resources. Optically, these can include near and distance magnifiers, reverse telescopes for field expansion, and UV protective tints to reduce photophobia.9 As the level of functional vision decreases, practitioners often discuss transitioning to other sensory modalities. This can mean utilizing tactile feedback, including but not limited to braille reading and white cane use, which is often used in conjunction with a dog guide after receiving orientation and mobility training.9 Patients will also increasingly rely on auditory access to text, which can be in the form of screen reading programs on our computers and phones, audiobooks for long-term reading, and assistive technology devices with text-to-speech functionality.9 Additionally, several phone applications are beginning to utilize artificial intelligence to improve text, object, and scene recognition capabilities.10

The term legal blindness was developed by the American Medical Association in 1934 and incorporated into the Social Security Act of 1935, part of a sweeping set of laws passed by Franklin D. Roosevelt to establish a base level income for Americans who are unable to work.11 Legal blindness was initially defined as having a visual acuity of 20/200 or poorer in the better seeing eye or having a visual field no greater than 20 degrees in any meridian in the better seeing eye with a Goldmann III4e or III4e equivalent stimulus. Since then, the definition has been updated due to the advent of logarithmic visual acuity charts to include any patient with a visual acuity poorer than 20/100 in their better seeing eye.12 Benefits vary depending on a patient’s work history, if they choose to continue working, and on their level of income, but patients meeting the criteria for legal blindness may be eligible for monthly social security disability insurance payments, supplemental security income payments, and enrollment in Medicare before the standard age of 65.11 The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and Americans with Disability Act of 1990 further codified the protections and rights given to the legally blind.12 Today, patients meeting criteria for legal blindness in the United States are eligible for income tax exemptions, disabled persons parking placards, and alternative transportation resources that vary greatly by state and city. Additionally, legal blindness is a federally protected status and discrimination against the legally blind is against the law, making a designation of legal blindness useful when pursuing accommodations in the workplace or in school. For patients with peripheral vision loss and visual acuity loss that are each independently insufficient to warrant a legal blindness designation, the Social Security Administration also established a separate designation titled “visual disability.” While it is unclear what, if any, differences exist in benefits or payments received between patients with legal blindness and visual disability, these designations are considered functionally equivalent and can be used to qualify patients for many of the same benefits listed above.2

One complication in determining legal blindness or visual disability in patients with retinitis pigmentosa that was not encountered in this case is that the width of peripheral islands of vision along each meridian are included when calculating the extent of the visual field and can occasionally disqualify patients. In cases like these, alternative criteria can be used utilizing automated perimetry that likely will not capture peripheral islands of vision. If a Humphrey Field Analyzer 30-2 or 24-2 threshold test shows the widest diameter of visual field surrounding fixation is no greater than 20 degrees, the patient will also qualify for legal blindness.2 In these cases, a decibel value of 10dB is equivalent to a III4e stimulus, so a decibel value of 10 dB or greater is considered a seeing point (this value differs between alternate automated perimeters like an Octopus).12 If patients still do not meet legal blindness criteria, they can be assessed for an alternative criteria for visual disability known as visual impairment, which utilizes static perimetry and is similarly detailed in the Social Security guidelines on disability eligibility.2

Conversations surrounding legal blindness and visual disability are highly individualized and nuanced depending on the patient’s own grief process, including their acceptance or denial of their vision loss. In some cases, patients may be actively seeking out a legal blindness designation due to the benefits it provides. In others, this designation can be a strong emotional burden, especially initially. It may force patients to acknowledge or confront their vision loss in ways they haven’t previously had to, and some patients can internalize this designation, as well as the social stigma that can come with it, and develop a sense of hopelessness, shame, or self-consciousness. It is imperative that in these cases providers dispel misconceptions surrounding the term legal blindness and clarify its role purely as a medico-legal definition that entitles them to additional governmental support and not a personal label or commentary on their worth or functionality. Providers should also be aware of what mental health resources, including talk therapy and support groups, are available locally for patients who are struggling to come to terms with their vision loss.

Conclusion

In summary, retinitis pigmentosa is a progressive condition that requires continued monitoring, allowing low vision providers to base recommendations on the current level of vision. As vision loss progresses, magnification tools and non-visual access to print may become necessary. Goldmann Visual Fields are often the most useful tool for monitoring peripheral vision loss in patients with retinitis pigmentosa and for determining eligibility for designations of legal blindness or visual disability. The patient’s visual acuity and contrast sensitivity did not necessitate magnification at this time, but the extent of his visual field loss qualified him as having a visual disability and warranted the cessation of driving and a referral to orientation and mobility instructors.

Take Home Points

Goldmann Visual Fields are superior to monitor early peripheral vision loss in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. If there are no peripheral islands of vision and field loss has progressed within the central 30 degrees, conventional automated perimetry is appropriate.

For patients who do not meet the criteria for legal blindness, the Social Security Administration sets guidelines for an alternate legal designation, titled visual disability, which allows practitioners to combine visual acuity and visual field information. These designations are considered functionally equivalent.

Discussions surrounding the term legal blindness or visual disability should be held with compassion and empathy, and with the goals of the patient in mind. Patients meeting the criteria for legal blindness or visual disability in the US are entitled to benefits and exemptions that often vary depending on location