Introduction

Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) results from abnormalities in the myeloid cells within the bone marrow.1 Myeloid cells differentiate into erythrocytes, leukocytes, or platelets. These cells are responsible for oxygen transport, immune system function and hemostasis, respectively.1 The American Cancer Society estimates that approximately 20,800 people in the United States will be diagnosed with AML in 2024, with most of those cases occurring in adults. Greater than 50% of these individuals are projected to die from the disease.1 The eye is the only place in the body where nerves and blood vessels can be directly observed. Therefore, ophthalmic signs can precede systemic complications and can aid in the early detection of the disease.2 The retina is an intricate ocular structure. It is estimated that nearly 70 percent of all patients diagnosed with leukemia will exhibit funduscopic changes during the course of their disease.3 For patients that present with unexplained retinal hemorrhaging, remarkable changes in hemorrhaging compared to previous examination, or when the ophthalmic presentation does not correlate with the patient’s known systemic history, it is important to consider laboratory testing to determine if there is an infectious, inflammatory, neoplastic or underlying systemic etiology responsible.

CASE REVIEW

A seventy year old African American male presented as an emergency patient with complaints of redness, pain, sensitivity to light and complained of something blocking his vision in the right eye. The symptoms originally started three weeks prior and were not subsiding. The patient was also nauseated and tired, describing it as “flat on his back”. His finger-nails were brittle and his gums were tender to the point of not being able to wear his dentures. The patient had a systemic history of diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. These conditions were being monitored by his primary care physician (PCP) and controlled with the oral medications metformin (500mg twice a day), amlodipine besylate (10mg one time daily) and Simvastatin (20mg one time daily).

Entering visual acuity of the right and left eyes was 20/70-2 and 20/50, respectively. Preliminary testing which included pupils, extraocular muscle evaluation and confrontation visual fields all presented with normal findings. Intraocular pressures revealed asymmetric but normotensive readings of 18 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) in the right eye and 11mmHg in the left eye. Upon slit lamp examination, the patient was found to have a significant acute non-granulomatous anterior segment inflammatory reaction in the form of severe cells and flare accompanied with a mild hypopyon of the right eye. The bulbar conjunctiva had a moderate amount of injection and the cornea presented with mild edema as well as trace pigment on the endothelium. Gonioscopy revealed open angles without the presence of neovascularization.

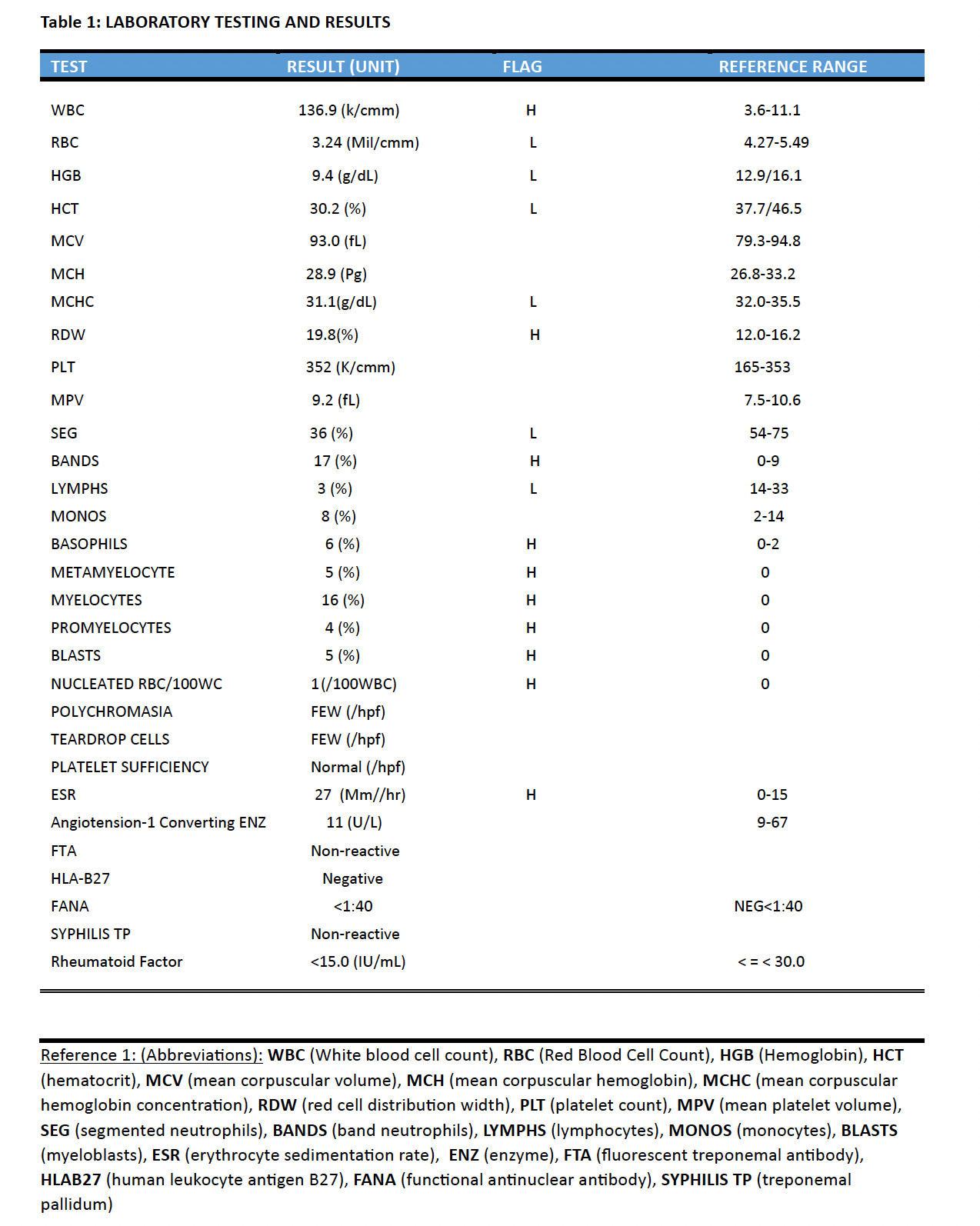

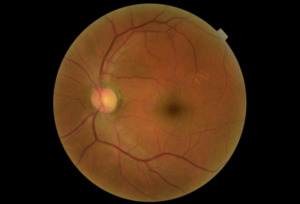

A dilated fundus examination was performed. The retina presented with a variety of diffuse hemorrhages varying from subhyaloid to intraretinal along with cotton wool spots and Rothspots in both eyes. The optic nerve presentation of each eye was normal and well perfused with no signs of abnormalities. At the completion of examination, the patient was diagnosed with an acute severe nongranulomatous anterior uveitis of the right eye and presumed severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy of both eyes. One year prior, the patient was seen for a comprehensive eye exam and was diagnosed with only mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, see Images 1-4 for comparison.

Due to the severity of the anterior chamber reaction and the progression of the retinopathy, a full blood panel workup was ordered to determine if the findings were attributed to an infectious, inflammatory, or a neoplastic etiology. Differential diagnoses to consider for an acute nongranulamatous uveitis are conditions associated with human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) such as, Reiter syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, ankylosing spondylitis, Behcet disease and psoriatic arthritis. Other etiologies that can contribute to an acute nongranulomatous uveitis are lyme disease and acute trauma.4 Fundoscopic manifestations with marked hemorrhaging in the presence of Roth spots and cotton wool spots should be suspected for vascular and hematological abnormalities such as diabetes, leukemia, septic chorioretinitis secondary to bacterial endocarditis, anemia and sickle cell disease.4 This patient’s PCP was alerted to the ocular findings and possible concerns. Included in the blood panel orders (Table 1, reference 1 for abbreviations) were: a CBC with differential, ESR, CRP, ANA, ACE, RA, HLA-B27 and FTA-ABS.

The patient was started on cyclopentolate 1% BID anddifluprednate every two hours in the right eye for the anterior segment findings and instructed to return in two days for a follow up. At the follow-up examination, the patient reported an improvement in his symptoms of pain and light sensitivity. He reported taking the medications as prescribed. Anterior segment findings showed minimal improvement and laboratory results were not yet received. The patient was advised to continue his drops with the current dosages and to return in five days for another follow-up visit.

At his second follow-up, now seven days following his initial presentation, the patient reported an improvement in both vision and pain. The vision in his right eye had improved one line to 20/60 and one line in his left to 20/40. He reported good compliance with both drops and his intraocular pressures were 13 mmHg in the right eye and 10 mmHg in the left eye. Anterior segment findings showed a resolved hypopyon with only mild cells remaining. Posterior segment fundus findings remained unchanged.

Laboratory results (Table 1) revealed a significantly elevated leukocyte count with elevated numbers of myelocytes and metamyelocytes. Specifically, the pathology report indicated moderate anisocytosis and mild hypochromasia of the erythrocytes. The elevated leukocyte count showed marked increase in mitosis, particularly the promyelocytes, mylocytes and blast cells of about 20%, the morphology of which is in favor of myeloblasts. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was elevated at 27 mm/hr; however, all other results pertaining to CRP, ANA, ACE, RA, HLAB27 and FTA-ABS were either negative, non-specific, or within normal limits. Through a system of co-management with the patient’s primary care physician, it was determined that the results were conclusive for a diagnosis of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. This not only explained his anterior segment findings and extreme shift in fundus presentation over a relatively short period of time, but also the systemic symptoms he was experiencing. The patient started taking imatinib mesylate (440mg p.o.) once a day as prescribed by his PCP. The patient was advised to discontinue the cyclopentolate drops but to continue the difluprednate while tapering down to one drop every four hours. A one week follow-up was scheduled.

At follow-up examination, he reported that he was compliant with the prescribed treatment, and noted significant improvement in both pain level and clarity of vision. Visual acuity improved to 20/25-2in the right eye and 20/25+2 in the left. The anterior uveitis resolved and his intraocular pressures were 15 mmHg in the right eye and 13 mmHg in the left eye. The patient was prescribed a one month taper of the ophthalmic steroid. He was seen by a retina specialist for further evaluation and management and was also being comanaged by both his PCP and oncologist. Five years after the initial leukemia diagnosis, the patient is alive and remains under the care of both a retina specialist and oncologist. He currently takes a 45mg daily dosage of an oral antineoplastic multikinase inhibitor.

Discussion

Leukemias can be categorized based on frequency of onset, acute vs chronic.1 Acute Myeloid Leukemia(AML) begins in the bone marrow stem cells that are responsible for developing into lymphocytesor myeloid cells.1 Lymphocytes supports our body’s immune system against disease and infection whereas myeloid cells develop into red blood cells, white blood cells or platelets. These particular cells are the ones that become abnormal in AML.

A comprehensive eye exam with anterior segment and funduscopic evaluation is necessary to determine if any ocular complications are presenting as a result of systemic disease. Ocular findings can be prevalent in 32%-35.5% of patients diagnosed with acute leukemia at the time of diagnosis.5 Ophthalmic manifestations can vary in presentation from anterior segment to posterior segment and are dependent on whether there is primary (direct) or secondary (indirect) infiltration.5 Primary is defined by direct infiltration of the cancerous blood cells that occur in three typical patterns: anterior segment with uveal infiltration, orbital infiltration and lastly, neuro-ophthalmic infiltration of the central nervous system. These latter, neuro-ophthalmic manifestations, lead to optic neuropathies with disc edema, cranial nerve palsies or orbital lesions with proptosis and periorbital edema.3,5,6 Anterior segment ocular manifestations are less prevalent but can include lid ecchymosis, lid ptosis, lid edema, proptosis, subconjunctival hemorrhages, conjunctival chemosis, uveitis and hypopyon.5 Although the occurrence of hypopyon associated with leukemia is rare, it is more common in acute versus chronic leukemia, and in general is considered an early sign of central nervous system involvement or systemic relapse.6

Of all leukemia related ocular involvement, retinal involvement or leukemic retinopathy is the most common, occurring in 50-70% of patients.3,6 These posterior segment findings are typically a secondary or indirect manifestation resulting from tributary hematological abnormalities caused by the leukemia.5 Leukemia can cause secondary complications such as anemia, thrombocytopenia, hyperviscosities, etc .2,7 In the retina, these findings usually manifest as retinal vascular changes including intraretinal hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, white-centered hemorrhages or Roth spots, as well as vitreous hemorrhaging or vascular occlusions.3,8,9 The retina is the most involved ocular structure and it is estimated that nearly 70-90 percent of all patients diagnosed with leukemia will show fundus abnormalities at some point during their illness..3 Fundus findings are more prevalent in acute versus chronic leukemias and in myelogenous versus lymphocytic. Therefore, AML is associated with the highest occurrence of retinopathy.3 Abu el-Asrar et al. retrospectively evaluated the prognostic importance of retinopathy in adult and pediatric leukemia patients. They reported that the three-month mortality rate of patents with cotton-wool spots is eight times higher than in patients without these retinal lesions.3,10

Conclusion

Treating anterior segment ocular manifestations of AML depends on the patient’s presentation and symptoms. Treatment can vary from observation to topical ophthalmic steroids. However, leukemic retinopathy is directly dependent on the treatment of the underlying cause, with systemic chemotherapy. Since direct evaluation of both the nerves and vasculature can be achieved in the eye, ophthalmic examination can provide early detection of systemic disease. An ophthalmic examination, therefore, may be the first indication of disease that leads to referral with the patient’s primary care physician for further testing. Although non-specific, a complete blood count can provide crucial information to the patient’s overall health. This test should be considered for clinical presentations that do not correlate with the patient’s known systemic history, such as, an acute severe non-granulomatous uveitis with hypopyon, unexplained retinal hemorrhaging or marked changes in funduscopic presentation when compared to previous examinations. Long-term prognosis for survival varies greatly on the subtype of leukemia involved, its cytogenic and molecular findings, the age of the patient affected and any comorbidities the patient may also be affected by.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are employed as optometric physicians for the Lance Corporal Dana Cornell Darnell VA Clinic affiliated with the William Jennings Bryan Dorn VA Medical Facility in Columbia, South Carolina. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Lance Corporal Dana Cornell Darnell VA Clinic in Greenville, South Carolina.

DISCLAIMER

The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs of the United States Government.

_(blue_arrows)_roth_.png)

_(blue_arrows)_roth_s.png)

_(blue_arrows)_roth_.png)

_(blue_arrows)_roth_s.png)