Introduction

Anemia affects more than 10% of the adult population over 65 years old. While nutrient deficient anemia makes up more than 30% of these cases, malignant etiologies such as leukemia must also be considered. Ischemic retinopathy can be a sign of anemic and hematologic disorders and may affect any ocular tissues. The clinical features of ocular ischemia, common hematologic disorders, appropriate lab testing, and co-management of these conditions are reviewed in this case report.

Case Presentation

A seventy-one year old white female presented for a comprehensive eye exam with a chief complaint of blurry vision. She noted the right eye (OD) was worse than the left (OS) and had started one month ago with significant worsening in the last week. The blurry vision was constant but seemed worse on her superior and right field of vision. Her last eye exam was two years prior and was significant for early nonexudative age related macular degeneration (NEAMD), immature cataracts, dry eye syndrome, and diabetes type 2 without ocular manifestations.

The patient’s review of systems was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes type 2 diagnosed in 2007, and obstructive sleep apnea. Medications included 10mg Losartan daily, AREDS 2 supplement twice daily, and pravastatin 40mg daily. Her diabetes was controlled with diet and exercise with a HGA1c range of 5.4-6.2% from 2007-2020; her latest lab value for HGA1c was 5.4% in 2020.

Her entering distance acuity with spectacle correction was OD: 20/30-2, OS: 20/25-2. There was no improvement with pinhole acuity. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light without an afferent pupillary defect. Confrontation visual fields were full to finger count OD, OS, and extraocular muscles had full range of motion without pain or diplopia.

Manifest refraction showed:

OD: -6.00-1.25x110 20/30+1

OS: -6.00-0.25x055 20/25-1

Slit lamp examination findings revealed moderate blepharitis with mild meibomian gland dysfunction. The cornea was clear without staining OD, OS. Sclera and conjunctiva were white and quiet without injection. Cataracts were present and were graded 1+ nuclear sclerosis with few vacuoles OU and a 1+ superior posterior subcapsular cataract OD>OS.

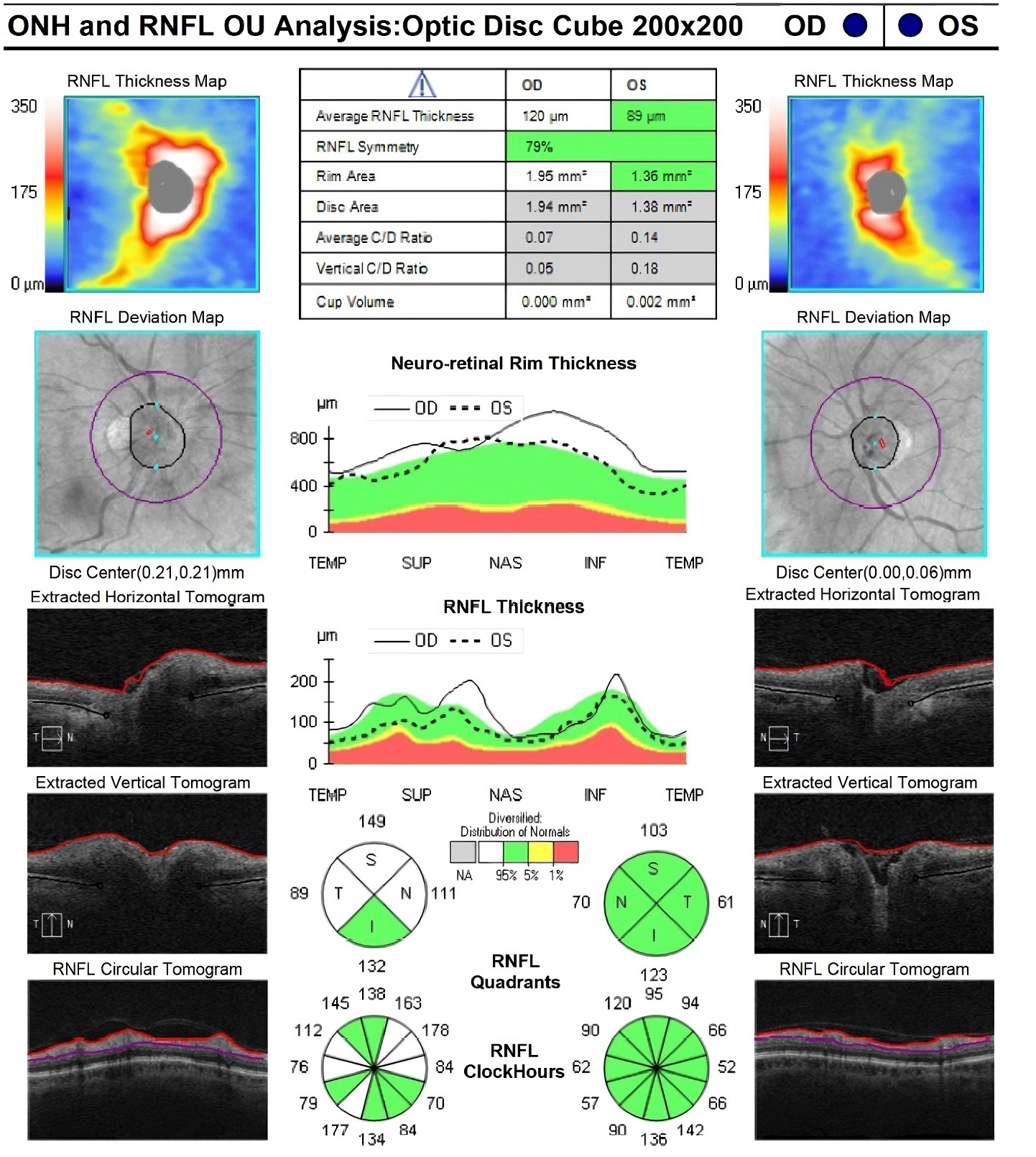

Posterior segment findings are illustrated in Figure 1. The right eye had few flame hemorrhages surrounding the optic nerve and mild disc edema. Her left eye had rare dot blot hemorrhages in the posterior pole. Both eyes had mild vessel tortuosity and mild retinal pigment epithelium mottling with few small drusen in the macula. With the presence of mild disc edema on funduscopic examination, optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the optic nerve was performed for a quantitative measure of edema (Figure 2). This confirmed the presence of unilateral optic nerve edema OD with elevated margins 360, greatest in the superior quadrant.

Given the patient’s systemic vascular risk factors and her ocular findings, differential diagnoses included:

-

Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) OD

-

Diabetic retinopathy

-

Hypertensive retinopathy

The main differential was an acute NAION OD as her fundus exam showed unilateral disc edema with peripapillary flame hemorrhages. The patient’s previously recorded small cup to disc ratio of 0.1 OU placed her at a higher risk for an ischemic event. She also had several vasculopathic risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, and newly diagnosed anemia. Additionally, her sleep apnea is also a condition which is known to increase the likelihood of NAION by inducing nocturnal hypoxia.

Diabetic and hypertensive retinopathy were considered lesser differentials given the presence of flame and dot blot hemorrhages. However, these were deemed unlikely as the patient’s diabetes was well-controlled (last hemoglobin A1c: 5.4%) and her blood pressure in office measured 129/82 mmHg with prior trends in normal range. Therefore, the prevailing diagnosis was NAION in the right eye as an indication of ischemic retinopathy OU from her new anemia diagnosis.

Further questioning revealed additional symptoms, recent fatigue over the last several months, intermittent numbness to her right arm and leg, and periods where her vision would “white out” for a few seconds.

With the addition of these neurologic and systemic complaints, the patient was sent to the emergency room for neuroimaging and lab work. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head showed no sources of bleeding or acute intracranial hemorrhaging. Lab testing revealed the following (Table 1).

The lab directly contacted the provider to report a critically low hemoglobin. Critically low hemoglobin values can indicate an increased risk for cardiac arrest if not treated emergently. The patient was admitted and underwent two blood transfusions to bring her hemoglobin value to a less critical range of 9.1g/dL.

During her admission, she was evaluated by hematology and diagnosed with macrocytic anemia based on her lab testing. She was prescribed B12 supplementation. Despite improved visual complaints, the patient remained symptomatic over the next two months for fatigue and intermittent numbness and tingling of her extremities.

Repeat lab testing was only slightly improved and a bone marrow biopsy was performed. Results of that test as described by pathology were “many abnormal mononuclear cells seen on smear; very few maturing myeloid cells are present.” These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia. She was referred to oncology and underwent three cycles of chemotherapy over a four-month period. She achieved remission after the third cycle. Eight months after her initial diagnosis, and four months after her remission, she was found to have recurrent AML on her bone marrow biopsy. Her hemoglobin again plummeted to critical levels of 5.7 g/dL. With limited medical options for the aggressive recurrence, the patient passed away less than a year after her initial eye exam.

Discussion

Anemia is a condition related to a decreased level of red blood cells, hematocrit, or hemoglobin as a result of either a deficiency or abnormality of production through erythropoiesis or a loss or damage to red blood cells through hemorrhage or hemolysis.1 Types of anemia are further categorized by etiology, size of red blood cells, and hemoglobin content.

The prevalence of anemia increases with age with over 10% of adults over 65 years of age affected and increasing to upward of 20% in those over 85 years of age.2 The most common forms are nutrient deficient (iron, folate, and/or vitamin B12), which make up roughly thirty percent of cases. While many cases of anemia are asymptomatic and require little management, new onset anemia with systemic signs and symptoms should be considered cancerous until proven otherwise.1

Common systemic signs and symptoms of anemia are outlined in Table 2. A comprehensive history should also be gathered including obvious bleeding, dietary deficiencies or abnormalities, abnormal stools, and any family history of hematologic or thrombocytopenic disorders.

Of great importance to eye care clinicians is that retinopathy is found in 28.3% of patients with anemia and increases to 38% in those with comorbidities of anemia and thrombocytopenia.3 Anemia leads to hypoxia as a result of reduced oxygen carrying capabilities of red blood cells to end tissues. When the hemoglobin level is below 8 g/dL, the risk of ocular ischemia and its manifestations increases.

Ocular manifestations can be an initial presenting condition in up to 90% of patients with an underlying hematological disease.4 Conjunctival pallor, frequent or non-resolving subconjunctival hemorrhages, or hyphema can be an indicator of severe anemia of the anterior segment of the eye. Most commonly though, ocular signs of anemia present in the retina. Although the exact pathophysiologic mechanism is not yet understood, it is thought to be similar to retinal ischemia of other vasculopathic conditions such as hypertensive retinopathy or diabetic retinopathy.5 Signs may present in any layer of the retina, choroid, or optic nerve and are correlated with the severity of anemia. Flame shaped hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, and Roth spots indicative of focal ischemia are common as well as tortuous vessels, attenuated arterials, and dilated veins.5 Less common findings include macular edema and exudate, anterior ischemic optic neuropathies, disc edema, and vascular occlusions.6

In patients with acute leukemia such as acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) or acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), ocular involvement was present in 42.85% to 52.7% of cases.7 Caused by malignant neoplasms of bone marrow and subsequent abnormal production of blood cells, leukemias affect multiple systems in the body, including the eye. Ocular involvement may occur by either primary leukemic infiltration or secondary involvement from systemic changes.8

Primary infiltration commonly affects three orbital entities: anterior segment uveal infiltration, orbital infiltration, and central nervous system infiltration including the optic nerve.8 These direct infiltrations cause ocular manifestations such as anterior chamber inflammation and hypopyons, proptosis, choroiditis and retinitis, cranial nerve palsies, and optic nerve edema.9 Secondary changes, as a result of systemic hematological changes such as anemia or thrombocytopenia, can appear as ocular manifestations as discussed above.

As ocular findings may precede systemic ones, early detection can help patients with an earlier diagnosis and affect survival rates, although ocular involvement is associated with a poorer systemic prognosis.8 Primary infiltration of ocular tissues is less common in acute leukemias and seen in only 16.7% of cascades according to Hafeez et al.7 Clinicians should be aware that retinal hemorrhages are the most common manifestation of leukemias as a result of secondary systemic changes.7

If ischemic retinopathy is suspected and out of proportion to already diagnosed or controlled systemic diseases, a further investigation of other potential pathologies should be considered. Lab testing such as a complete blood count with differential and nutritional labs such as iron, folate, and B12 may illuminate issues such as anemia or thrombocytopenia. Those with ocular findings affecting visual acuity such as macular edema may be referred to retina specialists for consideration of treatment such as anti-VEGF. If patients have concurrent neurological symptoms, a referral for a more urgent work up to the emergency room to consider imaging such as a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be indicated.

Conclusion

With up to 90% of patients demonstrating ocular manifestations as their initial presenting sign of an underlying hematologic condition, eye care providers occupy a crucial position in the timely diagnosis of these cases. Ocular and retinal ischemia can result in sign and life-threatening conditions if left untreated. Blood tests, including a CBC with differential and nutritional labs of B12, folate, and iron can help differentiate nutritional anemias from more malignant pathologies such as acute leukemias. Retinal hemorrhages are the most common presenting sign in anemia and acute leukemias and should be investigated in those cases with well-controlled or no vasculopathic risk factors. An interdisciplinary approach is essential for managing these patients, ensuring proper diagnosis and treatment of the underlying systemic disease.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the United States (US) Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

_and_mild_disc_edema_(stars).png)

.png)

_and_mild_disc_edema_(stars).png)

.png)