Introduction

A 67-year-old white male reported to the clinic with unilateral, sudden, painless vision loss from a right central retinal artery occlusion. In most cases, individuals who experience a CRAO have permanent monocular decreased vision with or without the complications this patient experienced. Not only is a CRAO vision threatening, but the underlying systemic diagnosis is life-threatening.

This case report highlights two unique presentations and complications of CRAO: box-carring and iris neovascularization. Box-carring or ‘cattle trucking’ is a less common finding of CRAO. The fundoscopic appearance presents as segmental blood flow, where blood columns are perfused in some areas with adjacent areas of nonperfusion secondary to an embolic event. The interrupted areas of blood flow increase areas of ischemic retina and potentially the development of retinal neovascularization. This case report reviews the necessary emergent stroke workup, reviews the etiologies of CRAO, and highlights the importance of early follow-up to evaluate for potential neovascularization of the iris, angle, and retina.

Case Report

Initial Visit

A 67-year-old white male presented for an urgent examination with the chief complaint of sudden, painless vision loss of the right eye approximately two hours prior to the exam. He denied all symptoms of stroke or giant cell arteritis. He reported compliance with 81mg aspirin daily and with his blood pressure medication (lisinopril 20mg) at night. The patient reported that he had received a full heart workup recently. His ocular history was significant for non-exudative age-related macular degeneration in both eyes. He reported compliance with taking an AREDs 2 formulation twice a day by mouth. His medical history was positive for COPD, carotid atherosclerosis, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. He reported smoking half a pack of cigarettes per day.

Case history revealed that the patient received a workup by a cardiologist two months earlier due to chest pain and shortness of breath. His stress test, fourteen-day event monitor, and electrocardiogram (EKG) were normal. His echocardiogram showed mild diastolic dysfunction and mitral valve stenosis. His carotid Doppler revealed some mild blockage in the internal carotid artery on both sides that was not severe enough for surgical intervention. His cardiologist had started the patient on anti-hypertension and breathing medications (carvedilol 25mg, albuterol sulfate 90mcg).

His best corrected visual acuity was hand motion at 5ft OD and 20/25 OS. Pinhole testing did not improve the vision in the right eye. Pupils were equal in size, round, and reactive to direct light, with an afferent pupillary defect in the right eye. Confrontation visual fields were restricted in all quadrants except the superior temporal quadrant in the right eye and were full in the left eye. Extraocular muscle function was full and smooth in both eyes.

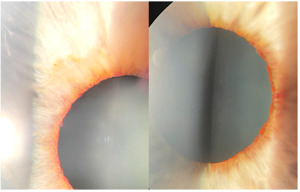

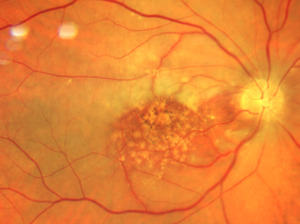

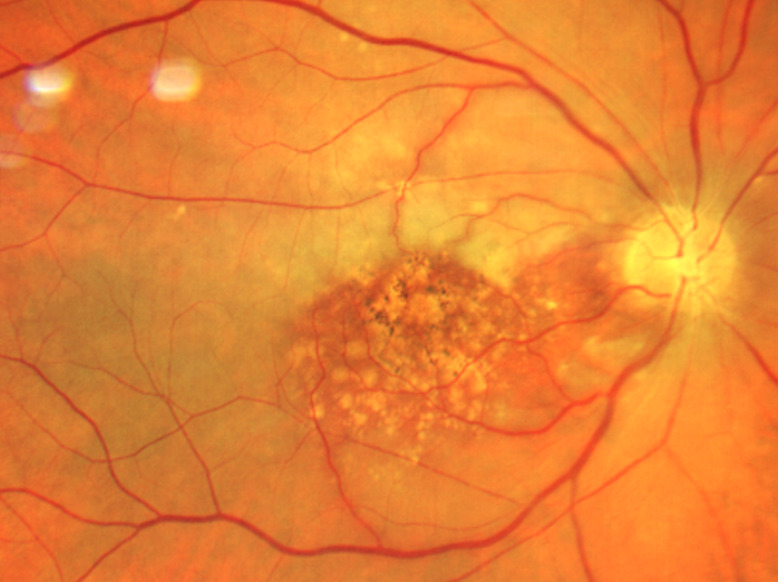

The slit lamp examination of the anterior segment revealed normal age-related findings in both eyes. Intraocular pressures were 14mmHg OD and 13mmHg OS. Posterior segment examination of the right optic nerve revealed edema with non-distinct margins more notable nasally than temporally. The cup-to-disc ratio was .20 horizontally and vertically in each eye. The retinal arterioles of the right eye were attenuated with box-carring (areas of segmental interrupted blood flow) superior and inferior to the macula (Figures 1-3). The maculae were flat with large drusen. The pole of the right eye demonstrated retinal whitening.

Due to the box-carring of vessels, retinal whitening, afferent pupillary defect, sudden painless vision loss, and swollen optic nerve, the diagnosis of a central retinal artery occlusion right eye was made. A medical emergency was called. Ocular massage was attempted, and vision did not return. The patient was taken to the nearest hospital with documentation of findings, a description of the diagnosis, and a request for stroke work-up and testing to exclude giant cell arteritis. A follow-up was scheduled for the patient to return to us in 3 weeks.

Emergency Room Visit

The patient had a three-day stay in the hospital and received a stroke workup. His CBC revealed mild anemia, elevated triglycerides (197mg/dLH), slightly elevated CRP (.935mg/dL normal <1.0), and elevated ESR (30mm, which could be considered normal for the patient’s age). The CRP and ESR were not elevated to the extent that temporal arteritis was suspected. His bilateral common carotid artery was stenosed less than 50% and a moderate amount of calcific plaque was found in both carotid bifurcations (the most common area in the carotid arteries for plaque buildup). Mild atherosclerotic calcifications were present on the aortic arch and great vessel origins. CT of the head with and without contrast was normal.

It was also noted that “the proximal/mid right cervical vertebral artery is completely occluded; the right vertebral artery reconstitutes at the C4 level and is then patent into the posterior circulation.” Of note, at the patient’s initial exam, no signs or symptoms of vertebral stenosis were noted throughout the exam (ataxia, vertigo, nausea and vomiting, diplopia, trouble swallowing, and slurred speech).1,2 Isosorbide dinitrate 10mg, atorvastatin 40mg, and clopidogrel 75mg were added to his medications by the hospital physician.

Follow Up

The patient returned three weeks later for his follow-up complaining of mild, boring right eye pain that waxed and waned for two days. BCVA remained hand motion at 5ft OD and was 20/25 OS. Preliminary testing was the same as his initial exam. The slit lamp examination of the anterior segment was also unchanged except for the right iris where neovascularization was noted around the pupil margin 360 degrees (Figure 5). The anterior chamber of each eye was deep and quiet, and angles were open one-to-one ratio with an optic section both eyes. Intraocular pressures were 18mmHg OD and 17mmHg OS.

Neovascularization of the angle right eye was noted by gonioscopy in all four quadrants, greater in the superior angle. The angles of each eye were open to the ciliary body band 360 degrees. The posterior segment exam of the right eye revealed a distinct neural rim with mild diffuse optic nerve head pallor. No neovascularization of the disc or retina was noted in either eye. The macular appearance (drusen) remained unchanged in both eyes. Figures 6 and 7 compare the acute presentation and the post-ischemic event where blood columns were restored. The right retina was white outside the macula and the right arterial vasculature was re-perfused (box-carring resolved) but was significantly attenuated (Figure 7).

Brimonidine BID OD was started to lower intraocular pressure while neovascularization of the angle was still present, and the patient was referred within the week to a retina specialist for pan-retinal photocoagulation and intravitreal Avastin. The patient was educated that the goal of treatment was to prevent a painful blind eye.

Discussion

Acute non-arteritic central retinal artery occlusion was the primary diagnosis in this case. A CRAO is an acute ischemic stroke of the eye causing sudden, painless vision loss. The central retinal artery is the first branch of the ophthalmic artery and supplies the inner retinal layers of the eye. The occlusion of the central retinal artery and subsequent arterial blood loss causes the retina to become ischemic, and the retinal cells die resulting in permanent vision loss.2–5 CRAO is analogous to a cerebral stroke and often foreshadows a cerebrovascular or cardiovascular event.3,4,6,7

In cases of CRAO, patients must receive a stroke work-up and giant cell arteritis laboratory testing. A stroke work-up typically consists of angiography of the head and neck by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and its arteries, echocardiography, cardiac telemetry, and basic laboratory testing, including hemoglobin A1c, lipid profiles, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and complete blood count (CBC).4,7,8 ESR and CRP laboratory tests measure the level of inflammation in the body to determine the likelihood of underlying giant cell arteritis (GCA) as the cause of the CRAO. GCA is an ocular emergency and warrants immediate systemic corticosteroid therapy to prevent further vision loss and systemic complications.5

Box-carring with CRAO

In CRAO, the loss of arterial inflow to the retina is usually due to an embolus occluding the central retinal artery either before or after the entry of the artery through the optic nerve head. Emboli can be of several different etiologies, with cholesterol being the most common.3–5,9 Diagnosis of CRAO is usually made clinically, with a history of sudden painless vision loss accompanied by certain clinic findings that present in response to retinal ischemia.10 The most common finding associated with CRAO is an afferent pupillary defect, which occurs because the ischemic retina is no longer transmitting the signal through the optic nerve to the brain that light is present. The second most common clinical finding, present in up to 90% of patients on the initial examination with CRAO, is a cherry red spot, which is a reddish appearance to the central macula from the underlying choroidal circulation seen in contrast to the surrounding whitened retina.2,6,11 Retinal whitening, or opacity, which is seen in 58% of those with CRAO, is the whitish appearance of the swollen ischemic retina in acute cases. The inner retina atrophies when the edema subsides.

Box-carring is a relatively uncommon presentation with CRAO. Box-carring is the term used to describe retinal arterioles that have sections with a visible blood column followed by sections with no blood column (similar to box cars on a train). Box-carring is present in 19% of eyes within 7 days of the onset of CRAO.4 In addition to box-carring, arteriolar narrowing may be present. Marked stasis of the retinal arterial circulation via fluorescein angiography (FA) can help confirm the diagnosis if present and if FA is available.4 Optic nerve head edema, caused by disruption to the axoplasmic flow, is present in 22% of those with acute CRAO. The continued disruption in flow results in loss of axons and optic atrophy.2 Finally, emboli visible within the retinal arterial tree is another clinical sign of CRAO, present in 20% (with a higher incidence in those with branch retinal artery occlusion).

Our patient did present with a vision decrease and an afferent pupillary defect. However, due to our patient’s extensive macular disease and the presence of a cilioretinal artery, a cherry red spot was not readily evident. Neither was the retinal whitening very prominent at presentation. As a result, our acute case presented with the most prominent posterior segment clinical sign being the box-carring of the retinal arterioles above and below the macula rather than the usual, more common signs of retinal whitening and cherry red spot.4,9,10 Our patient also presented with the less common presenting finding of optic nerve head edema.

Risk Factors

Men have a higher incidence of CRAO than women, and the incidence increases with age. Overall, CRAOs are rare, estimated at 1.80 per 100,000 persons per year.4,6,9 Systemically, CRAO is associated with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, vasculitis, smoking, and cardiovascular disease including carotid artery disease, coronary artery disease, and atrial fibrillation.4,7,11 Significant ipsilateral carotid disease is the most common risk factor in these patients, followed by atrial fibrillation.4,7

Etiology of Emboli

Emboli from the heart and the carotid artery are the most common cause of RAO.11 In the heart, emboli are more likely to originate from the aorta followed by the mitral valve.11 Our patient had known carotid disease prior to his CRAO. Testing following the CRAO found less than 50% stenosis of the internal carotid arteries bilaterally. He had 100% occlusion of the proximal/mid-right cervical vertebral artery. In addition, an echocardiogram following the CRAO showed that the patient also had calcific plaques in the aorta and larger vessels adjacent to the heart. Thus, in the case of our patient, the embolus causing the CRAO could have originated from either the carotid arteries or the heart.

Of note, the absence of abnormalities on carotid Doppler evaluation does not rule out the carotid arteries as the source of embolism. It has been found that ocular arterial occlusions are microembolisms broken off from plaques, and plaque can be present with or without significant carotid artery stenosis.11 As noted earlier, emboli are not commonly seen on the fundus exam of a patient suffering from CRAO. Indeed, if the embolus is occluding the proximal part of the retinal artery (behind the exit of the artery from the optic nerve head), the embolus will not be visualized on fundus examination.11

Complications

Neovascularization of the iris is rare overall but is most common in patients with diabetic retinopathy, ocular ischemic syndrome, and central retinal vein occlusions.7 The incidence of neovascularization post-CRAO ranges from 1% to 20%.4,9 Most anterior segment neovascularization occurs within 2 weeks of the CRAO event.4,9

The reason for neovascularization of the iris secondary to a central retinal artery occlusion is controversial. In central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), there is chronic retinal hypoxia, but in CRAO there is acute retinal infarction.4,9,12 The chronic hypoxic situation in CRVO produces vasoproliferative factors (VEGF) over time and the VEGF induces new vessel growth.4 The situation is different with a CRAO. The central retinal artery supplies the inner retinal layers and once the blood flow is obstructed by an embolus, the retina essentially dies. The acute nonviability of retinal tissue does not allow for the formation of VEGF. For this reason, it is believed by some that neovascularization after retinal artery occlusion is due to underlying ischemic diseases besides the RAO itself, such as underlying diabetes or ocular ischemic syndrome.4,7 Alternately, recent studies have published reports of ocular neovascularization after RAO without evidence of underlying ischemic disease. A retrospective study of 214 CRAO eyes revealed a 10.9% incidence of iris neovascularization with carotid artery stenosis in only half of all NVI cases.4,9,11 As noted above, our patient’s carotid workup revealed only mild findings and he was not diabetic. Although neovascularization post-CRAO is a matter of debate, is it commonly agreed that the most important factor for developing NVI is chronic retinal ischemia.4

Of note, this patient did have vision remaining in the superior temporal quadrant of his right eye post-CRAO suggesting that some retinal tissue was still viable. Our patient did have a cilioretinal artery that likely served as an alternative perfusion source supplying a small area of the macula. Because a fluorescein angiography was not performed, it is unknown how much of the retina was perfused following the CRAO. Any remaining area of viable retina could have released VEGF resulting in neovascularization.

Ocular Management

There are no established treatments for acute retinal artery occlusion that consistently allow for the return of visual function. Classical and conservative treatments such as ocular massage, lowering intraocular pressure with various methods, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and intra-arterial tissue-type plasminogen activators have not been proven effective.7 Prompt systemic examinations and triage are the best treatment for the patient.

Although relatively uncommon, iris neovascularization following CRAO can cause neovascularization of the angle, subsequent neovascular glaucoma, and a painful, non-seeing eye. Because iris neovascularization tends to occur within two weeks following the event, the follow-up visit should be around this time. Patient education is important: patients need to understand the need to return for evaluation even though the visual acuity is not expected to recover significantly if at all. Patients with iris neovascularization require a prompt referral to a retinal specialist for intervention.

Systemic Management

The incidence of stroke in patients post CRAO becomes 15% higher than those who do not suffer CRAO, with the incidence of cardiovascular events being greatest within the first thirty days following a CRAO.7,9,13,14 Patients with RAO are more likely to suffer from co-morbidities compared to the general population. Indeed, cerebral ischemia was found in 30% of patients post CRAO.7,15 Thus, cardiovascular management, including stroke prevention strategies, is very important to establish early in the management of post-CRAO.

An important part of the systemic management for CRAO patients is smoking cessation. According to the American Heart Association journal, tobacco usage was documented more often with retinal artery occlusion hospital admissions versus hospital admissions for acute ischemic stroke.14,16 Smoking changes the body’s blood chemistry, increases the risk of blood clots, and reduces the amount of oxygen that reaches the body’s tissues.8,10 Smoking damages the heart and blood vessels, which can lead to cardiovascular disease – the leading cause of death in the United States. The patient who smokes also has a higher risk of experiencing a cerebral ischemic event. We educated our patient that in his case smoking cessation is crucial to attempt to slow down the progression of his systemic disease and his macular disease. Smoking cessation education and treatment is an essential part of managing CRAO patients who smoke and is critical in minimizing subsequent risk.

Conclusion

Although relatively unusual, box-carring of the retinal arterioles and optic nerve head edema may be presenting clinical signs of a CRAO along with an afferent pupillary defect, sudden painless loss of vision, retinal whitening, macular cherry-red spot, and retinal arteriolar attenuation. Indeed, box-carring, if present with a CRAO in an individual with significant macular degeneration, may be the most easily identifiable diagnostic posterior segment finding. In addition to the emergent stroke evaluation and evaluation for giant cell arteritis, CRAO patients also need to have a follow-up eye visit scheduled within weeks following the CRAO to evaluate for the development of neovascularization of the iris.