Introduction

Uveitis glaucoma hyphema (UGH) syndrome occurs from the mechanical irritation of the anterior chamber structures due to a displaced intraocular lens (IOL).1 Iris-lens irritation leads to the liberation of pigment cells, red blood cells, and inflammatory mediators into the anterior chamber. If left untreated glaucoma can result from their accumulation in the trabecular meshwork leading to an increase in intraocular pressure.1 This is the classic triad of uveitis, glaucoma, and hyphema syndrome. UGH may also present with other clinical signs such as a vitreous hemorrhage or cystoid macular edema.2 When UGH syndrome occurs in the presence of a vitreous hemorrhage, it is defined as “UGH Plus.”1 Herein we present a case of UGH Plus associated with a displaced posterior chamber intraocular lens (PCIOL) and review the diagnosis and management of this condition.

Case Presentation

A 75-year-old male presented to the eye clinic with a complaint of painful decreased vision and light sensitivity in his right eye for two days which he reported as progressively worsening, describing his vision as “foggy.”. His ocular history was remarkable for cataract extraction with PCIOLs in both eyes in the 1980s with surgical complications leading to an “inadvertent” filtering bleb in the left eye. His medical history included left-sided head trauma following a bike accident, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cerebrovascular accident. His current medications were Plavix, Trazodone, and Albuterol.

Upon presentation in the eye clinic, the patient’s best-corrected visual acuity (VA) was hand motion in the right eye, and 20/30 in the left eye. Pupils were equally reactive, with a peaked pupil in the left eye secondary to complications from cataract surgery. No afferent pupillary defect was present. The patient’s extraocular motility was unremarkable.

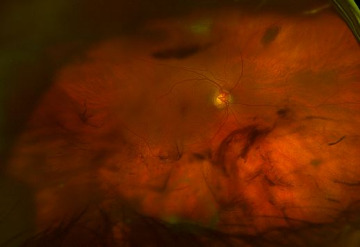

The slit-lamp examination of the right eye was remarkable for conjunctival injection, mild corneal haze and endothelial pigment, iris transillumination defects, 3+ cells and flare and a microhyphema with pigmented cells. The PCIOL was displaced inferiorly; the superior haptic was visible through the pupil and the inferior haptic was in contact with the posterior iris causing an inferonasal transillumination defect (Figure 1). The left eye was white and quiet with a superior filtering bleb. Intraocular pressures with Goldmann applanation tonometry were 18mmHg in the right eye and 11mmHg in the left eye. Dilated fundus examination revealed a 4+ dense vitreous hemorrhage that obscured the view of the retina in the right eye and a normal, intact retina in the left eye.

The patient was referred to the retina service for a same-day evaluation. A B-scan ultrasound ruled out a retinal detachment in the right eye (Figure 3). Laboratory testing for inflammatory disease was ordered including Toxoplasma titer, Lyme serology, ACE, serum lysozyme, RPR and FTA-ABS. The results of these tests were unremarkable. The patient was diagnosed with UGH Plus and prescribed topical prednisolone acetate 1% every 2 hours while awake, and cyclopentolate 1% three times a day.

At one-week follow-up, the patient reported residual photophobia and prominent floaters in the right eye; VA improved to 20/50. There were 4+ cells (mostly pigment cells) and 1+ flare in the anterior chamber. Intraocular pressure was 28 mmHg in the right eye and 12 mmHg in the left eye. Dilated fundus examination revealed vitreous debris consistent with resolving vitreous hemorrhage in the right eye. The right optic nerve appeared normal. The patient was instructed to continue using prednisolone acetate 1% every two hours while awake and cyclopentolate 1% three times per day in the right eye.

At two-weeks follow-up, the patient reported improved floaters in the right eye. His VA was 20/50 in the right eye. The anterior chamber reaction had improved to only trace flare and 3+ cells which were primarily pigmented. The intraocular pressure was 22mmHg in the right eye and 11mmHg in the left eye. Dilated fundus examination revealed presence of residual grey vitreous strands and a resolving vitreous hemorrhage inferiorly (Figure 2). The patient was instructed to reduce prednisolone acetate 1% to four times daily, continue using cyclopentolate 1% three times daily, and to return for follow-up in three weeks.

Six weeks after his initial presentation the patient reported an improvement in his symptoms.The visual acuity had improved from 20/50 to 20/30. The anterior chamber reaction had quieted to 1+ pigmented cells. The intraocular pressure was 20 mmHg in the right eye and 15 mmHg in the left eye. The patient was instructed to reduce prednisolone acetate 1% to twice daily and was switched to Atropine twice daily instead of cyclopentolate three times daily. At three months follow up, the patient remained stable, and his vitreous hemorrhage had nearly fully resolved.

Discussion

Mechanical chafing of the iris when an IOL is disclocated or subluxated can lead to UGH. For a diagnosis of UGH to be made there must be evidence of a malpositioned IOL. The iris trauma triggers an inflammatory cascade, pigment release, and bleeding in the anterior chamber causing uveitis and hyphema.1 This inflammation can also lead to secondary CME so a thorough posterior examination with OCT is warranted. The development of glaucoma may occur later on in the disease course due to persistent inflammation and chronic IOP elevation. The absence of glaucoma does not preclude a diagnosis of UGH. Symptoms of UGH syndrome include: blurry vision, transient vision loss, photophobia, and/or erythopsia.1 This may occur alongside iris transillumination defects, mixed cells in the anterior chamber, microhyphemas or hyphemas, elevated IOP, vitreous hemorrhage, and or macular edema.

Uveitis glaucoma hyphema syndrome – the triad of uveitis, glaucoma and hyphema in a patient that has undergone cataract sugery – was first described in 1978 by Ellingson.3 Since that time, the description and classification of UGH has evolved to adapt to changes in technology and to encompass other ocular findings. It can occur both with ACIOLs and PCIOLs, though the former is more common. Complications like UGH syndrome were initially attributed to poor edge finish and other manufacturing defects of early IOLs.4 With improvement in manufacturing techniques, the incidence of UGH syndrome in the United States has decreased from a mean of 2.2 to 3% to 0.4 to 1.2% over a one year period.1,5

Since 1978, two other variations of UGH have been defined: UGH Plus and IPUGH.1 UGH Plus is defined as UGH plus a vitreous hemorrhage. Incomplete Posterior UGH (IPUGH) is defined as bleeding into the posterior chamber (vitreous hemorrhage) with or without glaucoma and without uveitis.1 Coexistence of a vitreous hemorrhage or lack of either uveitis, glaucoma, or hyphema should not rule out a diagnosis of UGH as this condition can be diagnosed if any one of the three conditions in the triad are present in the setting of a dislocated IOL.

Management

UGH and UGH Plus syndromes can be managed medcially with topical therapy or surgical intervention. As in this case, a cycloplegic agent can be used to help stop intraocular bleeding by stabilizing the blood-aqueous barrier.6 Anti-inflammatory medications such as steroids can be used to treat uveitis, and if there is CME present adding an NSAID is important.7 If intraocular pressure is elevated, a standard approach of IOP lowering medications can be used; however, providers may choose to avoid prostaglandin analogs due to their pro inflammatory properties.7 Surgical intervention for elevated IOP, such as trabeculectomy, is also an option. A surgeon may also choose to reposition or exchange the lens if the patient’s acuity is very poor or the intraocular bleeding is not successfully treated with topical medications. In patients with UGH syndrome undergoing IOL repositioning, the surgeon should ensure the IOL is positioned away from the posterior iris and ciliary processes, due to risk of recurrance of UGH post-operatively.8

Conclusion

UGH syndrome has evolved into more than uveitis, glaucoma and hyphema occuring in the setting of a displaced intraocular lens. UGH syndrome with associated vitreous hemorrhage is a newly described variation known as UGH Plus. This patient’s condition was managed conservatively with topical therapy. Modern advancements in IOL design and surgical techniques have lowered the risk for dislocation of IOLs and subsequent UGH syndromes.7

__likely_accumulation_of_re.jpg)

_and_dislocated_pciol_(blue_a.png)

__likely_accumulation_of_re.jpg)

_and_dislocated_pciol_(blue_a.png)